Limmer Education

by Chris Ebright

Our articles are read by an automated voice. We offer the option to listen to our articles as soon as they are published to enhance accessibility. Issues? Please let us know using the contact form.

The United States is aging. The number of Americans aged 65 and older is projected to double from 46 million to more than 98 million by 2060. It will be the first time in history that the number of older adults outnumbers children under age 5.

They will also live longer than ever before. Today, one out of every four 65-year-olds will live past age 90.1

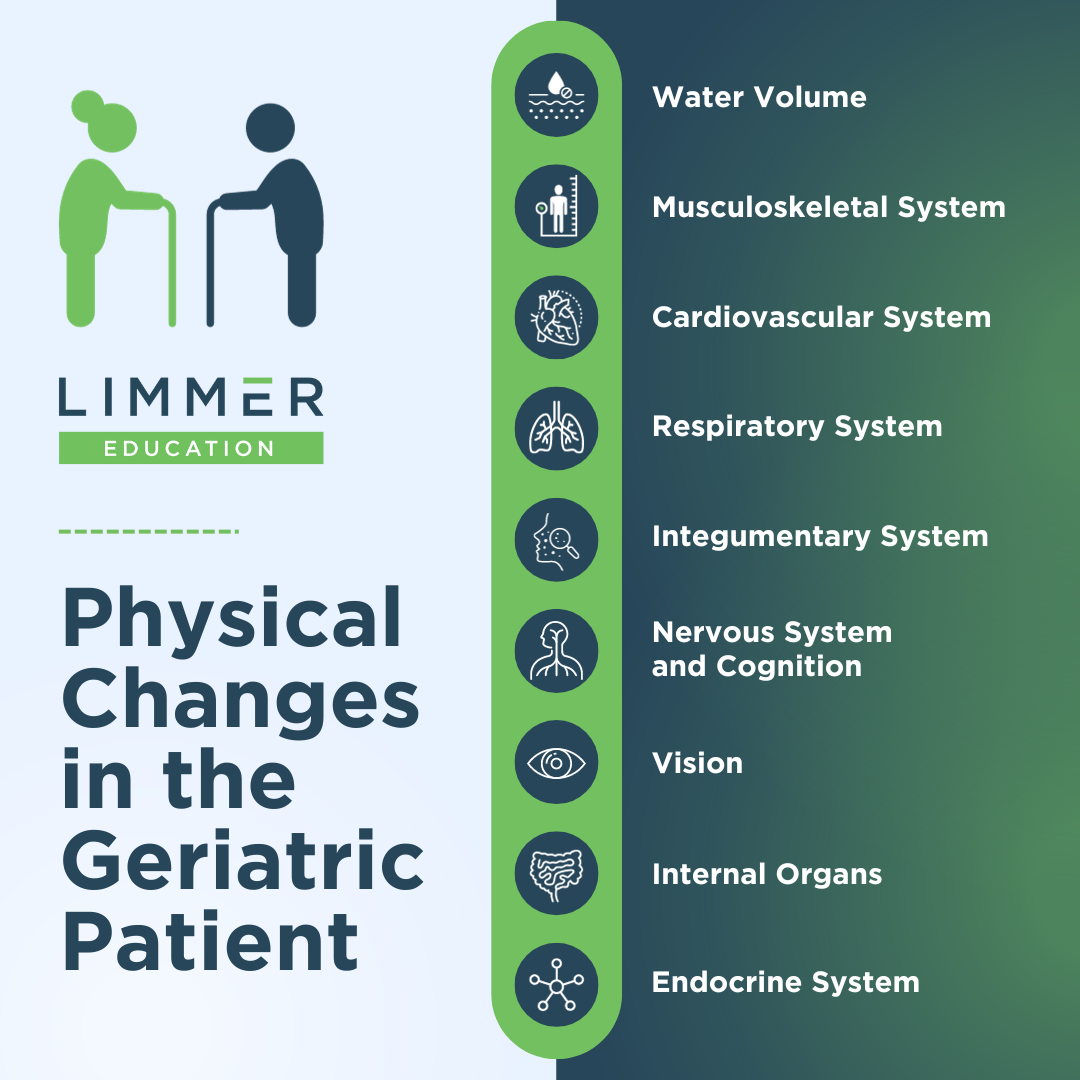

Older adults are unique in medical and trauma-related emergencies, as their anatomy and physiology are in a complex, ever-changing state at the structural, functional, and molecular levels. Diseases interact with pure aging effects to cause geriatric-specific complications. EMS professionals should be aware of these changes to correctly assess older patients, as they can mask underlying severe pathology.

First, let's look at what happens to overall body composition. The total body water volume naturally decreases as one ages, predisposing a geriatric patient to a higher likelihood of dehydration. This can cause a relative "thickening" of the blood, promoting clot development and making it harder to circulate. Stroke, renal failure, a pulmonary embolism, and myocardial infarction may result.

An older adult's muscle and skeletal mass diminish over time, leading to balance problems, causing falls and dislocations/fractures from what appear to be minor mechanisms of injury. Muscular strength decreases, and movement becomes restricted, affecting posture, venous circulation, and preload. Being unable to get outside and exposed to sunlight, the geriatric patient may develop vitamin D deficiency – compromising bone density and increasing the likelihood of fractures and dislocations.

In addition to lack of movement, aging has many inevitable consequences on the cardiovascular system. Baroreflexes become less aware of blood pressure changes, leading to a lack of compensatory increased heart rate. Decreases in the number of myocardial muscle cells, overall blood volume, and response to beta-agonist stimulation diminish an elderly patient's cardiac output. Decreased preload, increased afterload, and slower blood flow are consequences of increased thickness of the arterial and venous walls. Combined, these deficits of aging can lead to hypertension, congestive heart failure, orthostatic hypotension, myocardial infarction, aneurysms, and syncopal episodes – to name a few.

The respiratory system is not spared when it comes to aging, either. Quite often, older adults claim a respiratory ailment as their chief complaint.7

Atrophy of intercostal muscles, decreased lung tissue elasticity, diminished chemoreceptor sensitivity to changes in oxygen and carbon dioxide levels, a smaller number of alveoli, and less vital capacity and tidal volume all contribute to increased work of breathing, hypoxemia, and hypoxia. Combined with poor circulation, internal respiration becomes compromised, leading to hypercarbia and acidosis. Diminishment of the protective cough mechanism increases the risk of pneumonia and bronchitis and makes the geriatric patient more susceptible to aspiration and foreign body airway obstruction.

Next, let's consider the changes within the integumentary system. As we age, the subcutaneous skin layer is thinning, resulting in less cushioning and insulation from the cold. The number of blood vessels decreases, delaying delivery of nutrients and slowing an immune/repair response. This leads to slower wound healing, which can precipitate the onset of sepsis. The skin layers above also become thinner, increasing the likelihood of ulcerations, skin tears, and deeper-than-normal burns. Over time, as the number of sweat glands diminishes, the removal of excess body heat is compromised. The loss of blood vessels and superficial circulation increases the geriatric patient's likelihood of developing heat exhaustion or heatstroke.

Ageism and stereotypes are pretty common among the older population. They often refer to the diminishment of an older person's mental acuity – "it's just a part of getting old." This may be somewhat true for some, but not all geriatric patients have diminished acuity. Many have good, if not excellent mental capacities very late in life. However, the natural breakdown within the nervous system will notably affect some of your older patient examinations. Cerebral mass decreases, and cranial space increases. This makes geriatric patients susceptible to concussion, bruising, bleeding, and intracranial pressure changes. Atrophy of the cerebellum can manifest as impaired balance, causing a fall.

Within the brain, the number of dopamine receptors declines over time. Depression, with resultant increases in alcoholism and suicide, becomes evident. The speed of nerve impulse transmission slows, increasing reaction time, possibly resulting in a motor vehicle accident if the person is still driving. Memory decline sets in, causing dementia and poor adherence to taking medication. The inevitable declining number of cerebral ependymal cells diminishes cerebral spinal fluid volume. Lack of CSF allows greater force to be applied to the brain and cerebral vessels, leading to head injuries from even minor mechanisms. CSF also functions to maintain homeostasis of the interstitial fluid of the brain.8

Consequently, a low CSF level will compromise normal cerebral and cranial nerve function. Poor circulation from increased blood-brain barrier permeability and arterial wall thickness also compromises cerebral and cranial nerve function. The resultant deficits you assess in an older adult may be in their taste and smell, decreasing appetite, and leading to malnutrition. Nerve damage causing high-frequency hearing loss is associated with a higher risk of dementia, social isolation, depression, and injury-causing falls.9

It also makes it harder for an elderly patient to understand words and speech. Thus, you may have to alter how you communicate with your geriatric patient.

Every person will have some degree of visual loss naturally. However, within this population, a higher incidence of cataracts and glaucoma is notable. This vision impairment, especially when combined with a low-light environment, can cause many issues for your patient. Some of these include:

Medication dosing errors due to their inability to read labels properly.

Loss of 3-dimensional vision and poor depth perception = falls, fractures

Loss of independence = depression, suicide

Aging effects on the GI tract, liver, spleen, and pancreas also have many negatives. Decreased circulation to the intestines causes numerous issues, including malnutrition from lack of effective absorption and constipation from decreased peristalsis. Gastric emptying time increases with many older people, potentially increasing the risk of aspiration and development of gastritis or peptic ulcers, both of which can lead to internal bleeding. Liver malfunction can cause serum drug metabolite levels to rise above normal, increasing the risk of adverse drug effects (even if the patient is compliant with their medication dosing regimen). Deficits in the spleen cause decreased vitamin B12, iron, and calcium serum levels, all potentially compromising nutrition, bone density, and hemoglobin's effectiveness in carrying oxygen.

Dysfunction of the endocrine system, including the pancreas, has many widespread effects. Lack of insulin production combined with increases in insulin resistance increases the risk of diabetes, hyperglycemia, dehydration, and abdominal fat mass. The natural decline of other organs within the endocrine system decreases estrogen, testosterone, melatonin, growth hormone, vitamin D absorption and activation, and aldosterone levels. Sleep disorders, bone density, strength decreases, electrolyte imbalances, dehydration, and an increased risk for heart disease and stroke could be part of your next geriatric call.

Although it is tempting to regard many of the so-called diseases of the senior population as being the end-stage of normal physiologic changes that occur with aging, a distinction between the attrition in function of normal aging and pathological states must be clearly delineated. To do otherwise jeopardizes a patient's prospect for receiving proper prehospital care.6.

American Psychological Association. (1998, April). Older adults' health and age-related changes. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/pi/aging/resources/guides/older.

Stefanacci, R. G. (2022, September). Introduction to geriatrics - geriatrics. Merck Manuals Professional Edition. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/geriatrics/approach-to-the-geriatric-patient/introduction-to-geriatrics

BMJ MSS. Physiology of ageing. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine. 2013;14:310–2.

Alvis BD, Hughes CG. Physiology Considerations in Geriatric Patients. Anesthesiol Clin. 2015 Sep;33(3):447-56.

Stefanacci, R. G. (2023, August 10). Physical changes with aging - geriatrics. Merck Manuals Professional Edition. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/geriatrics/approach-to-the-geriatric-patient/physical-changes-with-aging#v1130874

Boss GR, Seegmiller JE. Age-related physiological changes and their clinical significance. West J Med. 1981 Dec;135(6):434-40.

American Senior Communities. (2017, October 31). Top 10 health concerns for seniors: ASC blog. https://www.asccare.com/health-concerns-for-seniors/

Telano LN, Baker S. Physiology, Cerebral Spinal Fluid. [Updated 2023 Jul 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519007/

Kasper, Dr. (2022, October 14). Why are high frequency sounds typically the first to go in hearing loss? https://www.newyorkhearingdoctors.com/why-are-high-frequency-sounds-typically-the-first-to-go-in-hearing-loss/.

Limmer Education

Dan Limmer, BS, NRP

Limmer Education

Excellent information for EMR’s. It’s imperative to understand the changes the human body goes through as it ages, especially the stages in each system. I read everything and gained a lot of great insight into the elderly patients we see everyday.