The Story Behind the Picture

by Dan Limmer, BS, NRP

Our articles are read by an automated voice. We offer the option to listen to our articles as soon as they are published to enhance accessibility. Issues? Please let us know using the contact form.

There’s a shelf in my office where I keep copies of all the editions of all the books I’ve written. For me, each book carries memories—of the time when it was written, the curriculum that was in place at the time, and the advances in medicine that we were able to incorporate.

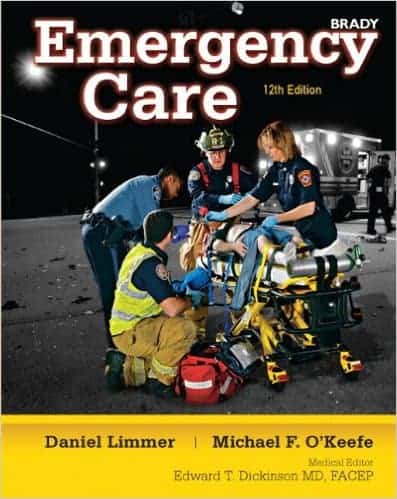

There’s one book, though, that evokes a dramatically different feeling. When I look at its cover, I feel a tug of sadness. The cover of the 12th edition of my Emergency Care EMT book features a color image of a scene that was recreated in the studio over a black-and-white image of an actual scene. The people in the color photo all convened one day in a warehouse in Portland, Maine, to recreate the emergency scene—EMTs, police officers and firefighters who’d all come to help us out with the photo shoot.

The person who can’t be seen in this picture is the patient on the stretcher. He was a young man named Greg Murphy. I didn’t know him well, but I knew he was well-liked and quite a character. At the photo shoot, he introduced himself to me and was sincere and serious. He told me how he wanted to always learn and how he hoped he could even learn at the shoot. I was impressed.

Greg probably had the most difficult task of all of us, because he had to lie on a backboard for the entire shoot. And it took hours. Afterward, we all said goodbye. The book was published. Greg went on to have an amazing fiancée, a beautiful child, and more EMS education.

Then he committed suicide.

Greg’s suicide rocked the local EMS world. Friends, family, and colleagues were devastated. Now, more than 4 years after his death, his Facebook page still gets frequent posts and tags. Sadness permeates the comments remembering him on the 4th anniversary of his death.

I contacted Greg’s fiancée before I wrote this post. I wouldn’t have shared it if she’d had an issue with it. But she didn’t, and she generously gave me permission to share Greg’s story. She told me that Greg had depression and bipolar disorder. Many people would be surprised at how common these conditions and others such as anxiety and PTSD are in EMS today. The people who live with them work with us, watch our backs, and share our everyday troubles and joys. Yet despite their close connections with us, their colleagues and partners, many of them don’t let us in to help with their pain.

I’ve wanted to write about this for years. I’ve wanted to share the story behind my book’s cover photo because it’s a perfect metaphor for how debilitating mental illness often plays out—in the EMS world, and in society as a whole. Because the story behind this photo is also, sadly, the story of many who live with chronic mental illness: We see the image that the person who’s suffering presents, but often we don’t know “the story behind the picture.” I share this story now to show that suicide in EMS is real, and that it affects our community in ways both subtle and shocking.

The tragedy of Greg’s suicide points to one with even broader implications: the tragedy that one helping professional who is suffering often doesn’t reach out to another helping professional for a lifeline, when we offer that same lifeline to strangers every day. When friends still post on someone’s Facebook page years after a suicide, “If you’d only asked, only let me know, I would have been there for you,” this is a tragedy.

In the time since Greg took his life, much has happened to bring awareness to the frequency and tragedy of suicide in EMS. The Code Green Campaign—formed after the death of another EMS provider—is a leader in this cause.

It was important to me to write this post so I could tell you the story of the person on the stretcher that day. A person who’s barely visible on the cover of my book but whose presence was and still is large in the hearts of many. One who is gone long before his time—before he could go out and do more good for people, before he got to know his daughter, before he had a chance to grow old with his fiancée.

For someone who’s living with a debilitating mental illness, surviving it often comes down to one well-timed and very simple act of kindness and support from a friend.

So today and tomorrow, please give of yourself to another. Give of your time and your caring. Reach out and be there for a colleague or friend. Don’t wait another minute.

Related articles

Dan Limmer, BS, NRP

Mike Miller

Comments

Leave a commentThanks for sharing Dan. It saddens me that we continue to have folks in the industry who believe we "baby" ourselves. It's important to continue to shine a light on this subject if even only to send a message to those who believe they are alone. They are not

Thanks for sharing, Dan. The struggle is real...every day.

Very well stated, Dan. Thanks so much for bringing this to the forefront.