When a Stroke is Not a Stroke: A Case Study

by Chris Ebright

Our articles are read by an automated voice. We offer the option to listen to our articles as soon as they are published to enhance accessibility. Issues? Please let us know using the contact form.

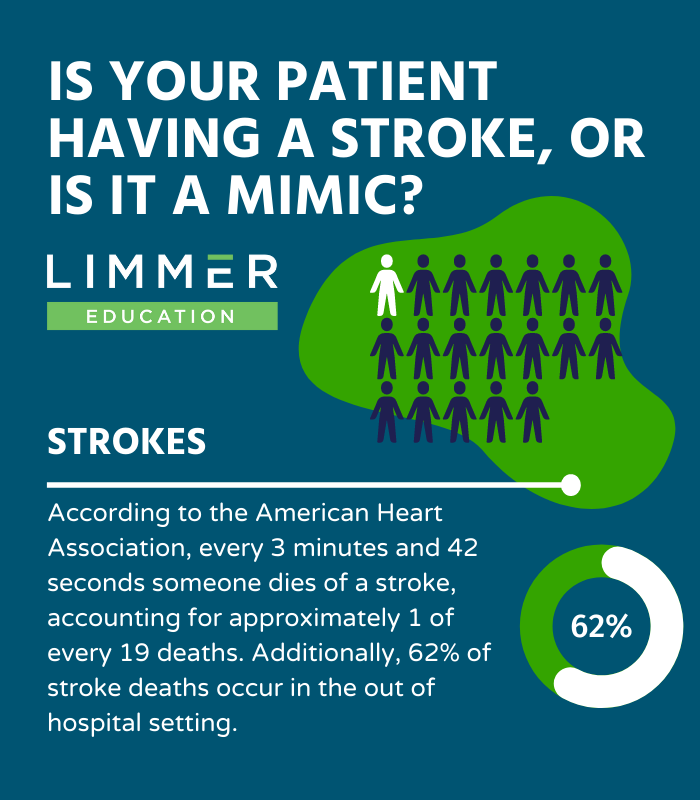

Stroke is a significant cause of mortality and morbidity in the United States, ranking fifth among all causes of death.1,2

According to the American Heart Association, every 3 minutes and 42 seconds someone dies of a stroke, accounting for approximately 1 of every 19 deaths. Additionally, 62% of stroke deaths occur in the out-of-hospital setting.3

A stroke classically presents as a sudden onset of a focal neurologic deficit, symptoms with an exact time of onset, abnormal eye movements, a diastolic blood pressure greater than 90mm Hg, and/or a history of atrial fibrillation.4

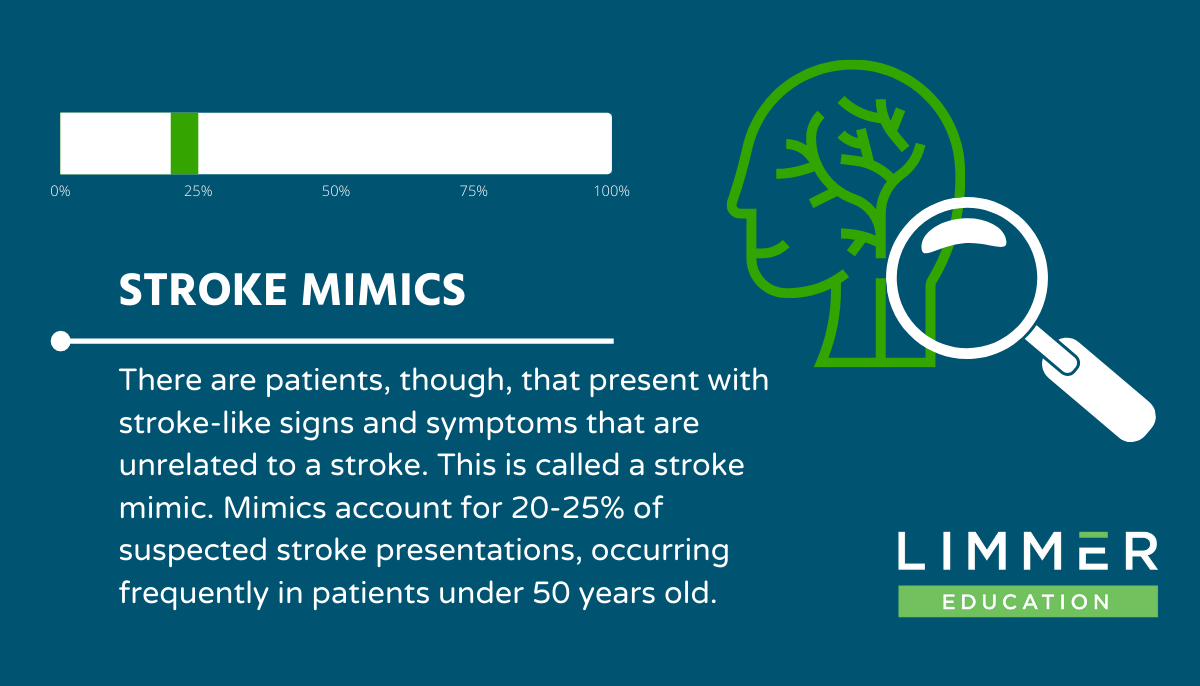

Stroke Mimics

There are patients, though, that present with stroke-like signs and symptoms that are unrelated to a stroke. This is called a stroke mimic. Mimics account for 20-25% of suspected stroke presentations, occurring frequently in patients under 50 years old.6,7

Many studies acknowledge that a decreased level of consciousness, a loss of intellectual function such as concentration, thinking, remembering, or reasoning, and normal eye movements are predictors of a stroke mimic.4

One particular study explained patients that present with a stroke mimic are younger and, more likely, female. None of these patients had a history of stroke risk factors, such as atrial fibrillation, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, renal failure, had smoked, or a poor diet.5,8

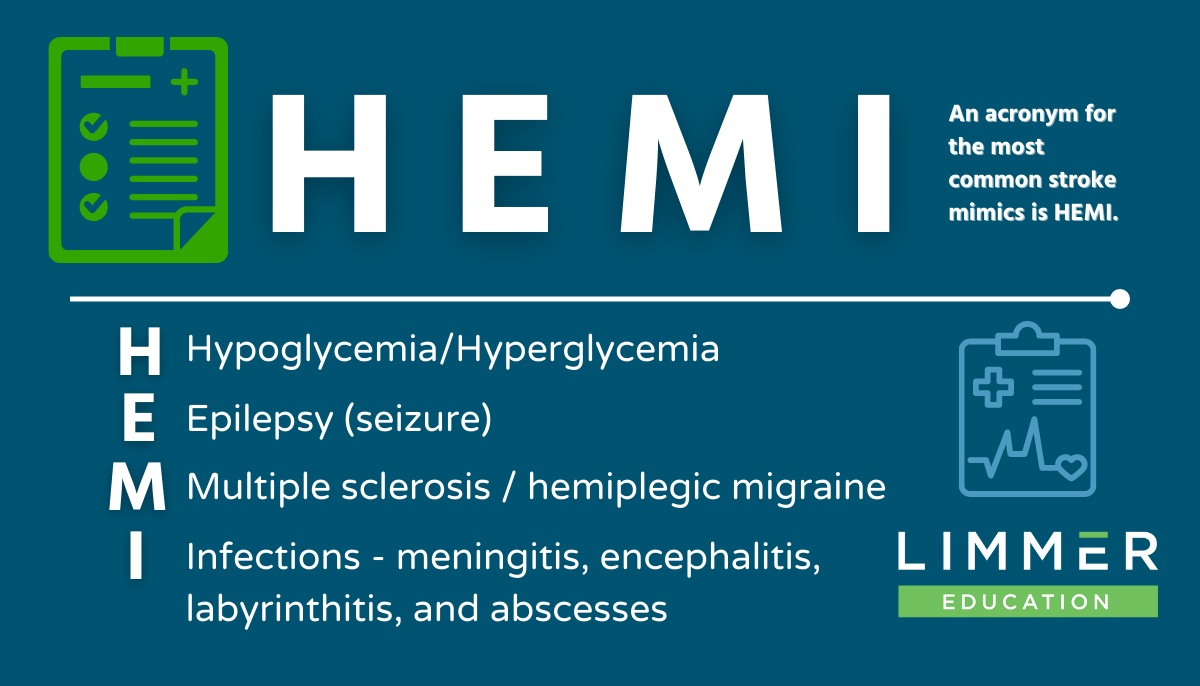

There are many conditions that can mimic a stroke: sepsis, syncope, intracranial tumor, conversion, factitious disorder, Bell’s palsy, or previous facial trauma. An acronym that addresses the most common mimics is HEMI.

H: Hypoglycemia/Hyperglycemia

E: Epilepsy (seizure)

M: Multiple sclerosis /hemiplegic migraine

I: Infections - meningitis, encephalitis, labyrinthitis, and abscesses

Stroke Mimic Case Study

EMTs examine a 50-year-old female experiencing a possible stroke. She is aware of the EMTs’ presence and oriented to date, day, time, and place. The primary assessment reveals no compromise in airway, breathing, or circulatory. A head-to-toe physical exam identifies: no head/neck trauma; bilaterally round and briskly reactive pupils, but the patient’s right eye is excessively tearing and she can’t move the eyelid; no JVD; anterior and posterior lung fields are clear with equal right and left-sided chest rise; abdomen is soft and non-distended; upper and lower extremities exhibit intact sensation, gross limb movement, and fine motor response. As a precaution, a Cincinnati Stroke Scale exam is performed. The patient is positive for slurred speech and complete right-sided facial droop, but negative for arm drift.

Vital signs: HR = 90, regular; RR = 16/min, normal depth; BP = 148/76 mmHg; SpO2 = 98% room air; CO2 = 39 mmHg; Temperature = 98.8o F; Blood capillary glucose = 95 mg/dL.

Discussion

Is she having a stroke, or is it a mimic? The EMS crew could speculate the possibilities, yet an important component of the assessment is still missing—a thorough patient history, ideally obtained from her.

When questioned, she states her right ear began hurting yesterday during breakfast, then she lost all sense of taste. Furthermore, her right eye has been tearing non-stop. This morning, the right ear hurt less but started ringing. Slurred speech and facial droop were still present. She says she takes hydrochlorothiazide, as prescribed, and has been taking an over-the-counter cold medication for the past three days.

History gathering is vital when differentiating a stroke mimic from a stroke. This patient’s two-day right-sided facial hemiparalysis, excessive tearing, tinnitus, loss of taste, and an intact extremity motor examination, leads the EMTs to suspect the patient is not experiencing a stroke. The crew transports the patient to a stroke center for definitive diagnosis, which later is confirmed as Bell’s palsy.

Conclusions

Stroke mimics are common. Differentiation between a stroke and a stroke mimic is difficult because of overlapping clinical presentations. This is even more challenging in the prehospital environment, due to the lack of diagnostic equipment. Ensuring the best patient outcome requires EMS professionals to conduct a thorough history and physical examination, and utilize all appropriate available tools. Suspected stroke mimics should be managed appropriately, but if in doubt, always expedite transport to the nearest stroke center.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Compressed Mortality File 1999-2009. CDC Wonder Online Database, Compiled for Compressed Mortality File 1999–2009 Series 20, No. 20, 2012. Underlying Cause-of-Death 1999–2009. wonder.cdc.gov/Mortsql.Html. Accessed June 1, 2015.

Kochanek KD, Xu JQ, Murphy SL, et al. Mortality in the United States, 2013. NCHS Data Brief, No. 178. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept. of Health and Human Services; 2014.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying cause of death, 1999-2016. CDC WONDER Online Database [database online]. Released January 2013. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html.

Libman RB, Wirkowski E, Alvir J, et al. Conditions that mimic stroke in the emergency department. Implications for acute stroke trials. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:1119-1122.

Merino JG, Luby M, Benson RT, et al. Predictors of acute stroke mimics in 8187 patients referred to a stroke service. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:e397–e403

Fernandes PM, Whiteley WN, Hart SR, et al. Strokes: mimics and chameleons. Practical Neurology 2013;13:21-28.

Segal, J., Lam, A., Dubrey, S. W., & Vasileiadis, E. (2012). Stroke mimic: an interesting case of repetitive conversion disorder. BMJ case reports, 2012, bcr2012007556. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-007556

Weiss J, Freeman M, Low A, Fu R, Kerfoot A, Paynter R, Motu’apuaka M, Kondo K, Kansagara D. Benefits and harms of intensive blood pressure treatment in adults aged 60 years or older: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:419–429. doi: 10.7326/M16-1754

Related articles

Dan Limmer, BS, NRP