Trusted Education for the Future of EMS

NREMT prep and classroom solutions that build better providers.

The Limmer Advantage

Made by NREMT Experts

NREMT Success

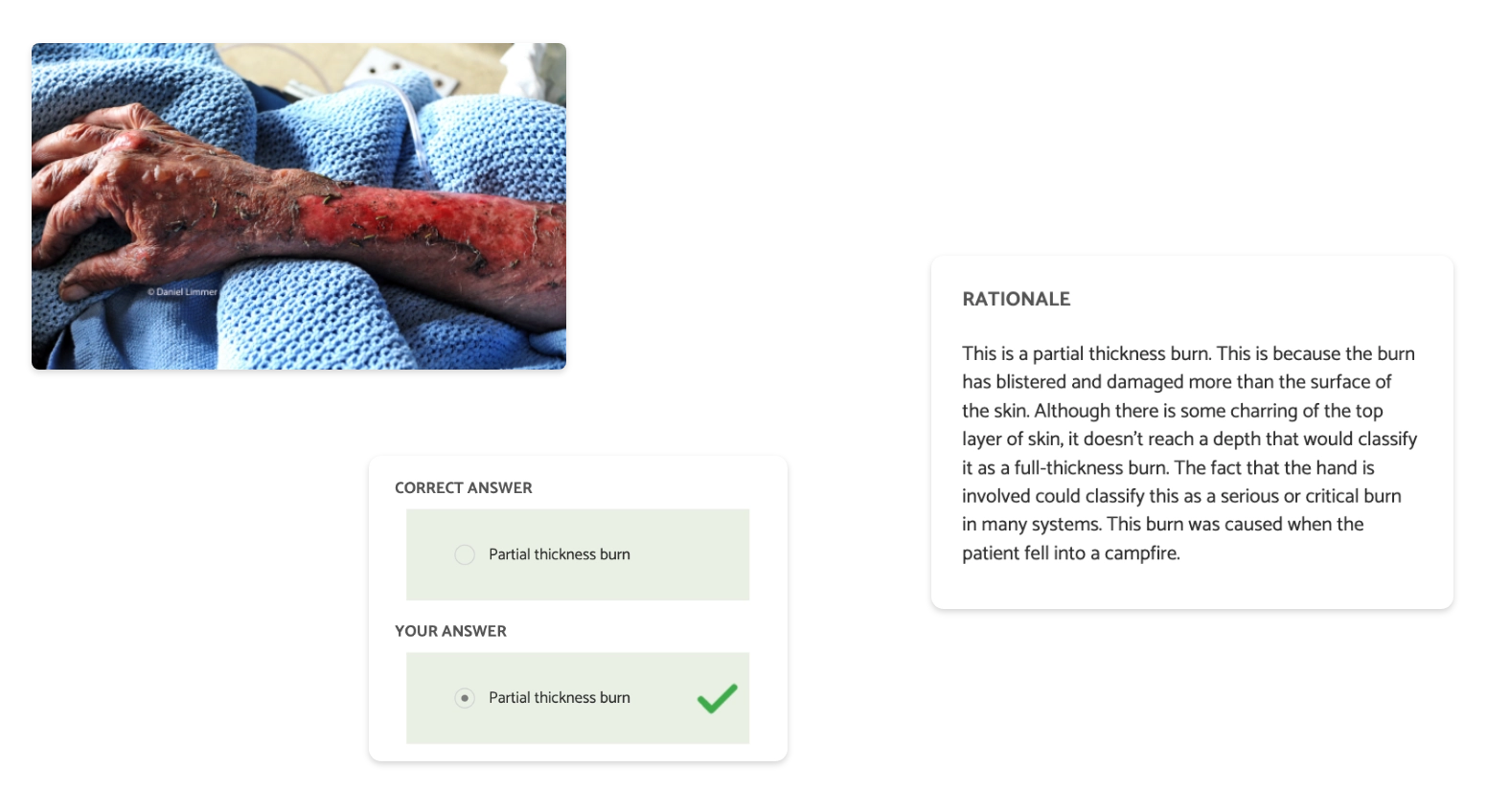

Help students succeed on their exams. Our apps focus on critical thinking, pattern recognition and pathophysiology.

Get startedAfter using your products and learning how to attack and understand questions I felt more confident than ever. The material you offer is amazing! It helped me to finally pass my NREMT! – Trevor D.

Find Your Match

We have a wide variety of apps for all different stages of your EMS education.

Use our product finderFrom our EMS Articles

Loved by EMS Students, Educators and Institutions

-

-

We've been telling our EMT students about the apps for studying for NREMT and have received nothing but positive feedback!!! All of the students from my campus that have utilized the apps have passed on their first attempt!

Lara OndruchEMT Instructor -

I have again successfully recertified by exam as an EMT by using your study resource. I felt well prepared for the exam and was only asked 70 questions.

Jim CoffeyEMT

-

-

-

I love your products. I downloaded the EMT PASS app and passed on the first try. Your questions and test taking strategies have great value to us active learners!

Brad IllingEMT -

[EMT PASS] has been invaluable! I've checked out a plethora of other test-prep apps, but THIS one is by far the BEST! Dan has a no-nonsense and direct approach that makes it very clear as to why the answers are what they are. Seriously, Best. App. Ever.

Toni TroneEMT

-

-

-

I recently let my registry lapse and had to take the new test. Because of your products, I walked into the test confident and had a very good handle on the necessary intellectual stamina it took to pass the new test. Your videos on how to interpret the question stems, and the new section that mimics the mechanics of the new test were instrumental in my preparation.

Jonathan "JoJo" AbuanProvider -

I passed! I am officially a Paramedic. I credit much of this success to [ParamedicReview.com]. This program teaches you how to study. Thank you again for your help over these past few weeks.

Austin McGonagleParamedic

-