Oxygen is the Wonder Drug No More

by Limmer Education

Our articles are read by an automated voice. We offer the option to listen to our articles as soon as they are published to enhance accessibility. Issues? Please let us know using the contact form.

Updated Resources:

Read the 2019 hyperoxia case study for a more detailed review of this issue. Also, check out the 2020 flowchart for better oxygen administration decision-making.

Last summer, we wrote a blog post in response to the 2010 AHA guidelines and the guidelines for oxygen administration in patients with ACS and stroke.

People were all over our Facebook posts and YouTube videos telling us we were wrong when we presented a scenario or test question that involved oxygen decisions. Patients with chest pain and an oxygen saturation at or above 94% probably won’t get any oxygen at all. If they are in significant distress we may administer oxygen—sometimes via cannula.

You would have thought we had said Johnny and Roy were just ambulance drivers! They were angry. They, often rudely, told us they would administer oxygen “because the patient needs it!” It didn’t seem to matter that oxygen in these patients may actually cause harm. This EMS1 article by Mike McEvoy helps to explain the concept very well.

5 years have passed since the 2010 AHA guidelines changed our approach to oxygenation.

The 2015 guidelines maintain the same position about oxygenation—and we still have people insisting on administering oxygen by NRB to chest pain patients with adequate sats. Even worse, we have educators teaching that same wrong approach.

As a refresher and because of the release of the 2015 AHA guidelines, we’d like to share our 4 Patients post again. It appears we still need it…

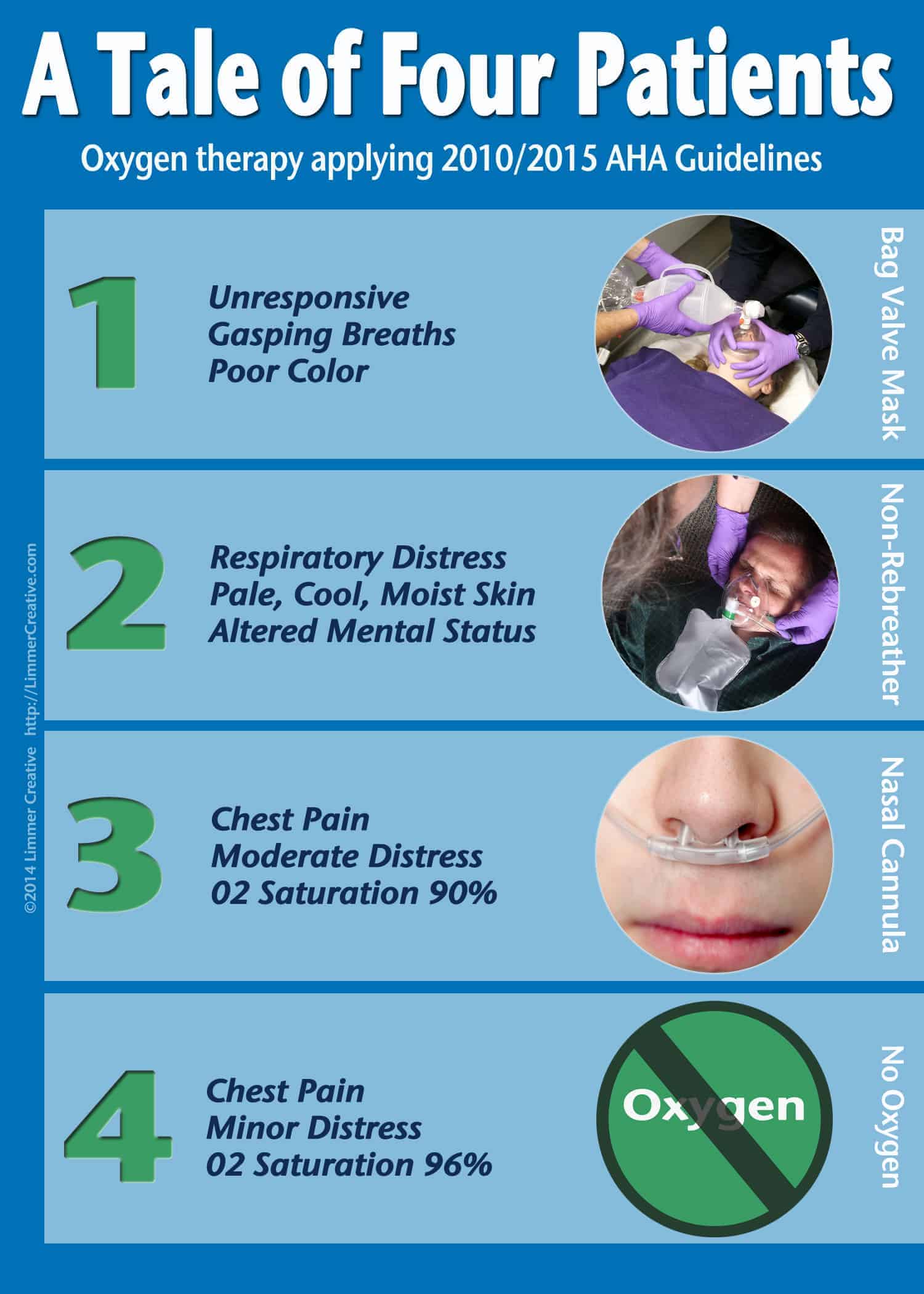

Patient #1 is in respiratory failure. He is ventilated with supplemental oxygen.

Patient #2 is sick. Very sick. Note his color and mental status. It really doesn’t matter what his saturation is. He is going to get oxygen by NRB.

Patient #3 has chest pain. In the past, we would have slammed the oxygen but now we take a more thoughtful approach. His sats are a bit low. A nasal cannula will bring that up nicely (we’ve forgotten just how much a nasal cannula can provide—and how comfortable it is for the patient). The concept of titration to 94% is important here.

Patient #4 – hold on to your seats – doesn’t get oxygen. He may have chest pain but his sats are good and he isn’t in distress. Monitor him carefully. If the sats drop or his condition changes you can respond appropriately. In this case oxygen may do more harm than good.

Oxygen is the wonder drug no more.

The take-home point: We used to call oxygen “The Wonder Drug.” It seemed that we could give it in wild abandon without worrying about consequences. There is no other drug in medicine that we think that about. We were wrong.

Related articles

Limmer Education

Limmer Education

Comments

Leave a commentRob just took the words right out of my mouth with his comment on evidence based medicine. I'm very new to this game - having earned my EMT-B patch this past Summer, but in class we talked at some length about evidence based medicine and changes to the field based on lessons learned recently in Iraq, etc. And this is all why I spend a certain amount of my free time on sites such as this. THANK YOU!!

Thank you for bringing this back to the front burner! Even though many protocols have been changed every service still has providers that "don't believe it!" As an evolving profession EMS must continue to research critical areas relating to emergency medicine every chance they get. Evidence based medicine is the only way we can grow and it is the only way scope of practice will change. After all, it's all about giving our patients the best care to enhance their chance of survival. The best ways to do that is to stay on the cutting edge of research and education. You can teach old dogs new tricks!