Trusted Education for the Future of EMS

NREMT prep and classroom solutions that build better providers.

The Limmer Advantage

Made by NREMT Experts

Clinical Depth

From Class to Field and Beyond

NREMT Success

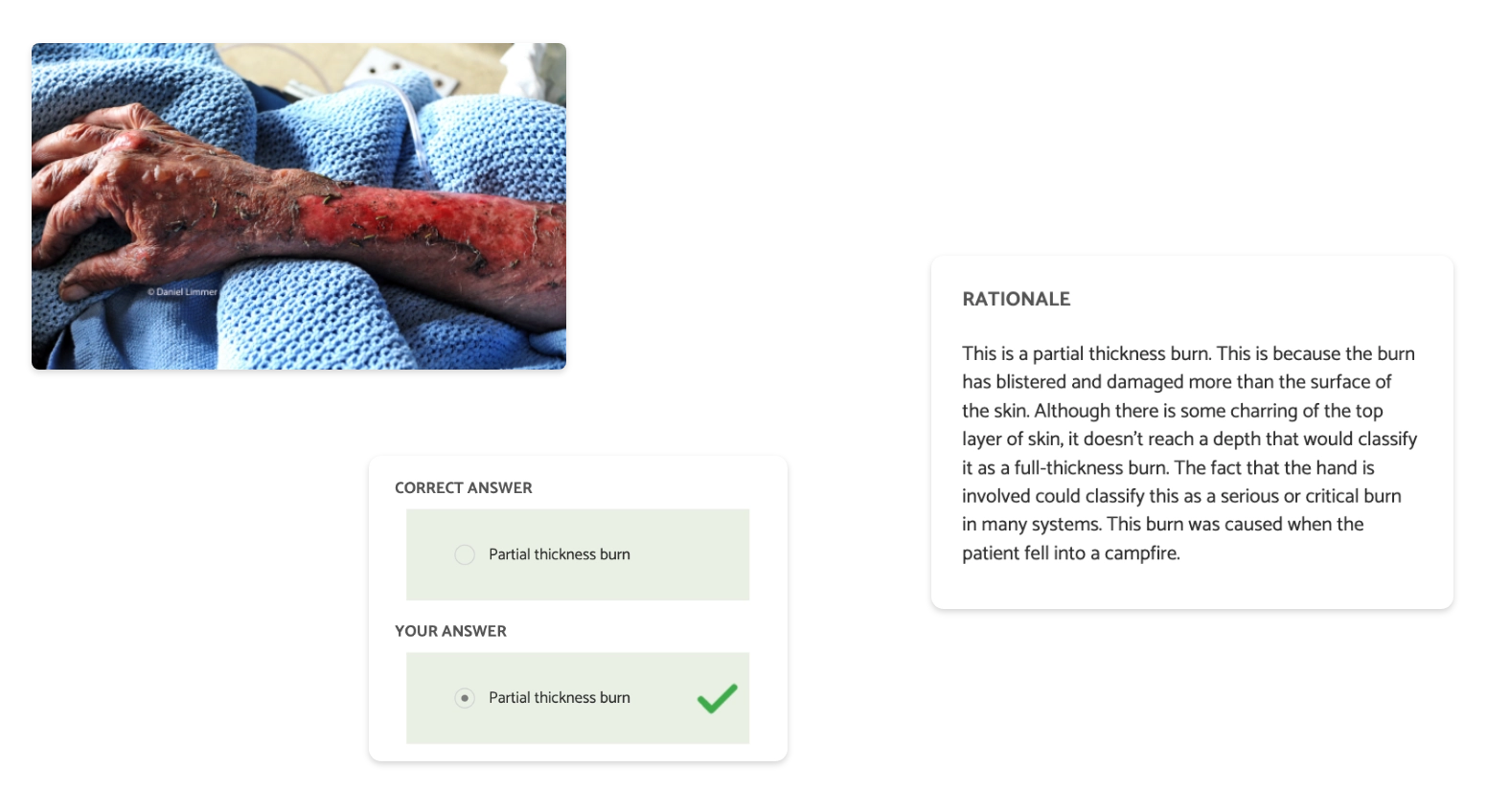

Help students succeed on their exams. Our apps focus on critical thinking, pattern recognition and pathophysiology.

Get startedAfter using your products and learning how to attack and understand questions I felt more confident than ever. The material you offer is amazing! It helped me to finally pass my NREMT! – Trevor D.

Educator Tools

We’re here to help you create a more dynamic, inspiring, and productive classroom.

Get startedI recommend Limmer resources to all my students. The pass rates are much higher and students have shown to be more efficient and effective in the field as a result. – Scott Stephens

Knowledge & Application

Our NREMT remediation courses help users pass… and give them relevant, deep understanding. 24-hr. EMT / 36-hr. AEMT

Get startedMy saving grace! I completed your online remediation and went in to take my third attempt and passed! Thank you!! – Sidney F.

CAPCE Approved

The 7 Things EMS podcast provides fluff-free, boredom-free CE for a variety of topics, from education to toxicology.

Get startedThank you for this podcast. I have learned so much and love that I can get CE for listening. – Julie R.

Find Your Match

We have a wide variety of apps for all different stages of your EMS education.

Use our product finderFrom our EMS Articles

Loved by EMS Students, Educators and Institutions

-

-

I earned my Paramedic license this morning!!! I truly believe I passed because I bought your [2-Hour NREMT Review Video]. I think I have ADHD and would rush through the test. Watching this video made me slow down read the question and chose the correct answer. Thank you, thank you, thank you!!!!!!

Angela SimpsonParamedic -

I recently let my registry lapse and had to take the new test. Because of your products, I walked into the test confident and had a very good handle on the necessary intellectual stamina it took to pass the new test. Your videos on how to interpret the question stems, and the new section that mimics the mechanics of the new test were instrumental in my preparation.

Jonathan "JoJo" AbuanProvider

-

-

-

EMT PASS was so thorough and difficult that taking the NREMT the 1st time was a breeze. Once I started getting the higher-level questions, I knew I was doing well. When it cut me off at 70 questions, there was no doubt in my mind that I had passed.

Larissa WilliamsEMT -

I took and passed my NREMT (1st try). I'm pretty sure EMTReview.com had a lot to do with that. Reading the rationale in all the practice/review test questions really helped, so THANK YOU.

Brian MenearEMT

-

-

-

I have again successfully recertified by exam as an EMT by using your study resource. I felt well prepared for the exam and was only asked 70 questions.

Jim CoffeyEMT -

Amazing program. The tests, the feedback, and the format is high level and I am grateful for the investment into this program.

Desmund ReidProvider

-