Limmer Education

by Chris Ebright

Our articles are read by an automated voice. We offer the option to listen to our articles as soon as they are published to enhance accessibility. Issues? Please let us know using the contact form.

The key to faking out the parents is the clammy hands. It’s a good non-specific symptom. I’m a big believer in it. Many people will tell you that a good phony fever is a deadlock, but you get a nervous mother, you could wind up in a doctor’s office. That’s worse than school. You fake a stomach cramp, and when you’re bent over, moaning and wailing, you lick your palms. It’s a little childish and stupid, but then, so is high school.”-Ferris Bueller

We all did it when we were younger, right? You didn’t feel like going to school, so you tried your best to convince your parents that you were just too sick. Faking a stomach ache was one of the easiest things to try, and in my case, it usually was effective (sorry, Mom). But what about that patient who truly has abdominal pain? Assessing it is one of the easiest and also one of the hardest things to do. Easy, because the exam takes under a minute; hard, because between what you assess and what the patient tells you, you’re left asking a lot of questions: do the symptoms, focused physical exam, and patient history suggest something life-threatening, or more benign? The degree of criticality is determined by getting answers to those questions.

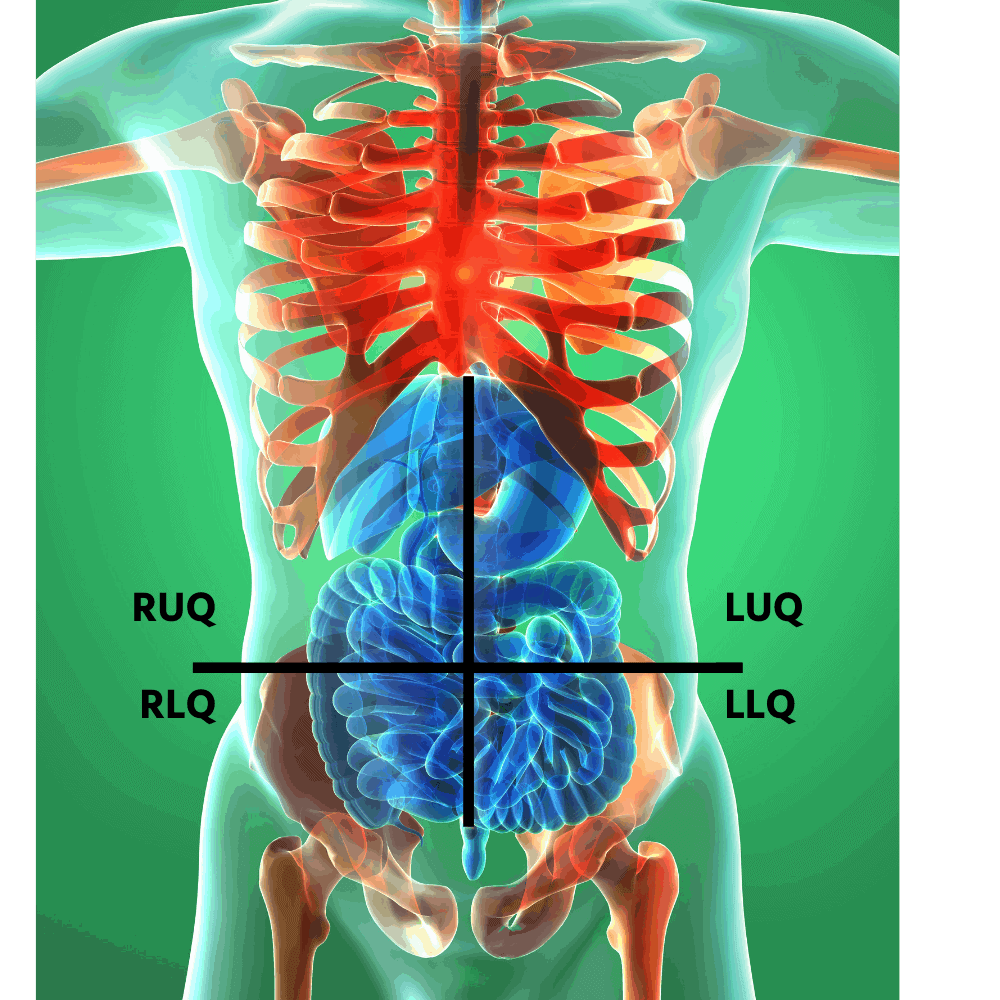

What helps to differentiate that diagnosis is knowing which organs exist in each abdominal quadrant. Physicians typically divide the abdomen into nine quadrants. Many EMS providers utilize a four-quadrant approach for ease and speed: two upper and two lower quadrants, each split into left and right. The quadrants are created by intersecting the horizontal and medial planes, using the belly button as the landmark where two planes cross.

The right upper quadrant contains: liver, stomach, gallbladder, duodenum, pancreas

The left upper quadrant contains: liver, stomach, pancreas, spleen

The right lower quadrant contains: appendix, reproductive organs, right ureter.

The left lower quadrant contains: left ureter, reproductive organs.

Additionally, all four quadrants contain portions of the small and large intestines. Located within the area behind the abdominal cavity, called the retroperitoneal space, is the inferior vena cava, abdominal aorta, lower portion of the thoracic spine, the kidneys (in the right and left upper quadrants, just under the diaphragm), and the lumbar spine.

Many organs overlap into an adjacent quadrant, or in the case of the intestines, all four quadrants, further complicating the formation of a definitive diagnosis. Instead of figuring out precisely what is wrong, follow this rule: after performing an abdominal pain assessment, determine the current degree of life-threat. In other words, does your knowledge of anatomy, the physical exam, patient presentation, and history lead you to believe in potentially fatal organ dysfunction, some type of “-itis” (i.e., tissue/lining inflammation/irritation), or something in between?

As you attempt to make that distinction, keep this in mind. Abdominal pain produced by organs, vessels, and tissue sometimes gives a false-positive impression. For example, a kidney stone has excruciating flank and groin pain as it travels through the ureters. However, as dramatic as it appears, the degree of life-threat is minimal. You may detect minuscule blood in the urine that results from abrasions to the ureter/urethra wall, but that is typically the extent. No life-threatening hemorrhage is present. Compare this to a patient complaining of a three-day, constant, dull, lower backache that radiates anteriorly to an area just above the navel. As much as he or she may dismiss this as a muscle strain, or perhaps gas, your astute EMS anatomy “Spidey-sense” alerts you to the possibility of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Which, if it ruptures, can be fatal within minutes. The moral of the story: Despite pain intensity, every structure within the abdominal area in question is in play until proven otherwise. Based on that, you now must determine what is the worst possible scenario?

The key to differentiating is to utilize as many assessment tools as possible. Example: It is crucial to not only determine where the abdominal pain originates, but also – what does it feel like, where does it radiate, and is there additional pain in another part of the body? An OPQRST exam will give you those answers. Onset is either sudden or gradual. Sudden abdominal pain typically indicates an obstruction or rupture, while a gradual onset indicates an inflammatory issue or distention.

A patient may tell you the pain Quality is sharp or dull. Sharp pain is called parietal (somatic) pain. Think of the “P” in parietal – the patient can Point directly (localize) at the source of pain. Or, think of the “S” in somatic = Sharp/Stabbing. This pain develops when the peritoneum (the membrane that lines the abdomen) and/or the abdominal muscles are irritated – typically from hollow organ contents or blood. Palliation (what makes it better or worse?) is sometimes apparent in patients with parietal pain. They usually present in a guarded/fetal position with shallow breathing. This position minimizes the stretch of the abdominal muscles and limits the diaphragm’s downward movement, which reduces pressure on the peritoneum and helps ease the pain. Examples causing somatic pain include:

a gastric or duodenal ulcer

ruptured ectopic pregnancy

ruptured aortic aneurysm.

Visceral pain develops when the nerves within the walls of an organ get overstretched. Because abdominal organs don’t have many nerve fibers, the pain tends to be dull/achy/gnawing, hard to locate and may be constant or intermittent. Think of the “V” in visceral. The pain is more Vague or Vast. Kind of like what we used to fake, right? Visceral pain is caused by:

inflammation

ischemia (restriction of blood supply to tissues)

mesenteric stretching (mesentery is the membrane fold attaching an organ to the abdominal wall; it contains blood vessels that supply the intestine)

distention of hollow abdominal organs

Examples causing visceral pain include appendicitis, cholecystitis, and diverticulitis.

The third type of abdominal-related pain is called referred pain. It is a pain felt in a part of the body other than its actual source. This pain occurs because of the nerve pathways wired between an abdominal organ and a different part of the body. When organ nerve pain is initiated, the signal travels to the brain, sending the same pain signal along a common connecting pathway to the other part of the body. The pain felt in the referred area usually is duller but constant. For example, a patient with gallbladder problems experiences right upper quadrant abdominal pain and also feels pain in the middle of the right posterior shoulder.

That all being said, here are some common abdominal ailments EMS is called for with a chief complaint of pain and the area(s) of symptoms.

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm – visceral pain typically; sudden parietal pain means impending rupture; originates in the midline, epigastric, lower back, and groin areas

Appendicitis – visceral pain originating in the midline of the abdomen; depending on the position of the appendix, the pain then refers to the RUQ, RLQ, LLQ, and even the epigastric region in some patients

Cholecystitis – visceral pain, typically; RUQ pain with referred pain to the right posterior scapula

Diverticulitis – visceral pain, typically; LLQ and the left flank of the abdomen

Ectopic pregnancy – visceral pain that will not last past the 8th week of pregnancy; sudden parietal pain should alert you to a rupture; pain will be in the RLQ or LLQ, depending on which fallopian tube is affected, rupture may produce referred pain to the same-side shoulder

Gastritis – can be either visceral or parietal pain, depending on the causative agent; RUQ and/or LUQ, typically referring to the back

Kidney stone – intermittent parietal pain as the stone moves/ureter spasm; pain the back, flank area, and eventually RLQ or LLQ

Pancreatitis – visceral, occasionally parietal pain; typically increases intensity after eating in the RQU and LUQ, referred pain may develop in the left lower back

Peritonitis – Initially, the pain may be visceral and diffuse; often, it progresses to steady, severe, parietal pain in all quadrants

Splenic rupture – parietal LUQ pain that refers to the left shoulder (Kehr sign)

As you can see, there are many different presentations for a patient experiencing abdominal pain. A definitive diagnosis is tough to establish and typically not necessary. Regardless of the cause, EMT management revolves around determining the degree of life-threat, making the patient comfortable, managing the basics, and delivering the patient to definitive care.

Until next time,

Chic, chic-a-chic-aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa…….

Limmer Education

Limmer Education

Dr. Bill Young